By Shazia Anwer Cheema

Each work demands to be seen without too much competition from other works of art and without a restrictive landscape setting!—–

Knud W. Jensen (1916-2000) Louisiana’s founder

Museums are one of my core areas of interest because I consider museums the best way of communication among the past, the present, and the future. How come a museum gives us a sense of the future and connects us with the time which is yet to come? Today’s Avant-garde can be the Classic of tomorrow and that is the reason I don’t miss museums of Modern and Contemporary Art.

Art historians believe that ancient paintings found in Egyptian pyramids were modern art of their era and their techniques were different than what archeologists found before the excavation of the pyramids.

During my recent summer vacation in 2022, I visited the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art which is in a Humlebæk 35 km outside the city of Copenhagen.

Louisiana Museum of Modern Art is a prestigious place for artists and art lovers, artwork around the world is continuously displayed and new artists can always count on finding a display area as long as their artwork is up to a certain standard. When I got to visit the Museum, exhibitions such as “As Long as the Sun Lasts”, “Forensic Architecture Witnesses”, “Dorothy Iannone”, “Diane Arbus Photographs” and “New acquisitions” were on display.

Founded by Knud W. Jensen, in 1958, the Museum had been promoting modern art, which until then had no special place in the Danish museums. During my visit, I experienced the art of Mel Bochner, Bunny Roger, Christina Quarles, and many others.

Museum’s first display was Mel Bochner’s “Amazing 2020” a monoprint in oil with collage, engraving, and embossment. Bochner is from the conceptual school of imagery and his work focuses on graphic imagery of poetry and is closely linked to a paired back stylized mode of expression. In 1969 he used a rubber stamp to imprint four words repeatedly “Language is not transparent”. After thirty years the artist recreated his work by using oil on paper; a series of works such as his famous “blah blah blah” and “amazing”.

Bunny Roger’s famous “Memorial Wall” presented self-detachment and attachment at the same time. Roger involves her followers in her artwork, she engages them to draw and paint leaves by using a particular kind of pen which has a special significance for her. She connects to the outer world at the same time by keeping herself isolated. Her choice of material varied from metal to wood and cloth. Her connection isolation dichotomy somehow provides her public empathy which she uses in her artwork.

Bunny Roger’s famous “Memorial Wall” presented self-detachment and attachment at the same time. Roger involves her followers in her artwork, she engages them to draw and paint leaves by using a particular kind of pen which has a special significance for her. She connects to the outer world at the same time by keeping herself isolated. Her choice of material varied from metal to wood and cloth. Her connection isolation dichotomy somehow provides her public empathy which she uses in her artwork.

The next display was of Christina Quarles’ “Hush now baby baby” acrylic on canvas. Quarles paintings are panoramic in bright acrylics of ambiguous, fragmented human figures. Her compositions are entangled, elongated, disfigured bodies having an interplay between canvas space, her brush stroke seems calligraphic at times. The bodies are always compact, multiple figures often entwined in ambiguous intimacy. References to art history abound- Picasso’s splintered perspective, Matisse’s colorful ornamentation, Dali’s soft, melting bodies, Hockney’s lushly eclectic style all infuse in Quarles compositions, representing fluid gender identities.

The next display was of Christina Quarles’ “Hush now baby baby” acrylic on canvas. Quarles paintings are panoramic in bright acrylics of ambiguous, fragmented human figures. Her compositions are entangled, elongated, disfigured bodies having an interplay between canvas space, her brush stroke seems calligraphic at times. The bodies are always compact, multiple figures often entwined in ambiguous intimacy. References to art history abound- Picasso’s splintered perspective, Matisse’s colorful ornamentation, Dali’s soft, melting bodies, Hockney’s lushly eclectic style all infuse in Quarles compositions, representing fluid gender identities.

Yoyoi Kusam’s “Gleaming Light of the soul” is one of the few permanently installed works, a space where walls and ceilings are covered with mirrors. The floor is a water surface, and you stand in the middle of the water on a platform. The small shining globes are infinitely reflecting and create a depth the end of which the eye only reaches because what we see seems to fade into the mist. The optic illusion created by optic depth gives the infinite width and depth to the space and the brain keeps on calculating and guessing how far and how deep the space would be.

Yoyoi Kusam’s “Gleaming Light of the soul” is one of the few permanently installed works, a space where walls and ceilings are covered with mirrors. The floor is a water surface, and you stand in the middle of the water on a platform. The small shining globes are infinitely reflecting and create a depth the end of which the eye only reaches because what we see seems to fade into the mist. The optic illusion created by optic depth gives the infinite width and depth to the space and the brain keeps on calculating and guessing how far and how deep the space would be.

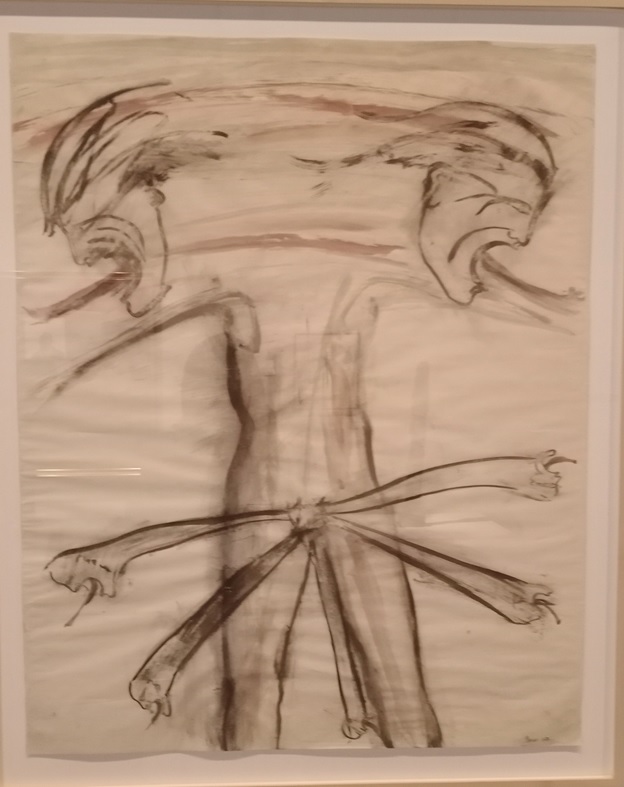

Nancy Spero was a feminist pioneer. Early in her career, in the 1960s, she abandoned painting, which she considered a symbol of male supremacy. From that point on, she worked exclusively on paper – a deliberate rejection of oil painting, which to her mind mainly served the need of male artists for demonstrative self-aggrandizement. Merging art-making with protest, Spero’s work takes a stand on issues like war and sexual equality. Over five years, starting in 1966, Spero created the War Series – more than 100 works relentlessly attacking the Vietnam War and the patriarchal world order that caused it. Key subjects include helicopters and bombs, the latter often in the form of male monsters. In Male Bomb, the male figure’s private part turns into a many-headed, snake-like monster resembling the rotor blades of a helicopter.

Nancy Spero was a feminist pioneer. Early in her career, in the 1960s, she abandoned painting, which she considered a symbol of male supremacy. From that point on, she worked exclusively on paper – a deliberate rejection of oil painting, which to her mind mainly served the need of male artists for demonstrative self-aggrandizement. Merging art-making with protest, Spero’s work takes a stand on issues like war and sexual equality. Over five years, starting in 1966, Spero created the War Series – more than 100 works relentlessly attacking the Vietnam War and the patriarchal world order that caused it. Key subjects include helicopters and bombs, the latter often in the form of male monsters. In Male Bomb, the male figure’s private part turns into a many-headed, snake-like monster resembling the rotor blades of a helicopter.

Regarding the medium of video as a kind of painting, Pipilotti Rist cultivates the aesthetic and expressive possibilities of the moving image. Her early videos provide punk responses to mainstream images and gender representations. Following her early works in the TV format, Rist’s camera becomes increasingly myopic, while projectors of all kinds liberate her video images from square screens. Gina’s Mobile, one of the artist’s many video sculptures, resembles both a model of the solar system and a modernist sculpture

Regarding the medium of video as a kind of painting, Pipilotti Rist cultivates the aesthetic and expressive possibilities of the moving image. Her early videos provide punk responses to mainstream images and gender representations. Following her early works in the TV format, Rist’s camera becomes increasingly myopic, while projectors of all kinds liberate her video images from square screens. Gina’s Mobile, one of the artist’s many video sculptures, resembles both a model of the solar system and a modernist sculpture

Dorothy lannone (1933) celebrates love and freedom in a narrative universe of text and images. Her exhibition presents work from the artist’s extensive output over the last six decades. Merging the personal and the mythological, lannone’s art is often based directly on her own life and experiences while drawing on a host of historical and literary references. Humour is invested in both verbal and visual details. Stylized in an almost pictogram-like manner, erotic scenes flow from historical representations of ecstatic unions across times, cultures, and religions. Iannone’s autobiographical images contain a wealth of references to antiquity, Greek vases, Egyptian art, Roman and Pompeian murals, the Indian Kama Sutra and tantra, Icelandic sagas, Christianity, Buddhism, world literature, and film history. Serving as muses, the artist’s lovers appear in her narratives.

Dorothy lannone (1933) celebrates love and freedom in a narrative universe of text and images. Her exhibition presents work from the artist’s extensive output over the last six decades. Merging the personal and the mythological, lannone’s art is often based directly on her own life and experiences while drawing on a host of historical and literary references. Humour is invested in both verbal and visual details. Stylized in an almost pictogram-like manner, erotic scenes flow from historical representations of ecstatic unions across times, cultures, and religions. Iannone’s autobiographical images contain a wealth of references to antiquity, Greek vases, Egyptian art, Roman and Pompeian murals, the Indian Kama Sutra and tantra, Icelandic sagas, Christianity, Buddhism, world literature, and film history. Serving as muses, the artist’s lovers appear in her narratives.

Several works feature the Swiss Artist Dieter Roth (1930-1998), who was lannone’s partner from 1967 to 1974.

Dorothy lannone was born in Boston but has lived and worked in Europe since 1967, mainly in Berlin. This is her first solo exhibition at a museum in Scandinavia.

This cookbook mixes existential thoughts and miscellaneous observations into real, neatly lettered recipes. A mayonnaise recipe includes the following observation, “WELL, GOD COULD be WOMAN. SORRY”

This cookbook mixes existential thoughts and miscellaneous observations into real, neatly lettered recipes. A mayonnaise recipe includes the following observation, “WELL, GOD COULD be WOMAN. SORRY”

A take on the classic cookbook format, the book is rich in details, sensuality, and statements about gender-served salty, sour, bitter, umami, and seductively sweet. It is a prime example of lannone’s many artist’s books.

A take on the classic cookbook format, the book is rich in details, sensuality, and statements about gender-served salty, sour, bitter, umami, and seductively sweet. It is a prime example of lannone’s many artist’s books.

In Mother’s Legs, the tree trunks are not alone in pointing back to the artist’s childhood home. They have been fitted with life-like casts of Kaari Upson’s own knees and those of her mother, transforming them into lifelike, fleshy legs. The traceries of insect tunnels running across their surface are convincingly transformed into broken capillaries on thighs. In this way, the work simultaneously contains a memory of a specific place and places us in the position of the small child, eyes at knee height, ready to grasp them. A haven of security – were it not for the violet, death-like hues and occasional blood-red paint residues that give the suspended legs a whiff of the abattoir, creating an eerie undercurrent.

The Iranian artists’ collective RRH lives in self-imposed exile in Dubai. The trio’s work explores homelessness and exile as lived experiences. The drawings depict the European refugee crisis from 2015 on as a tragic diaspora of mythic proportions. In a demanding, manual process, the three artists paint collaboratively on top of newspaper photos and clips from TV and YouTube. Refugee camps in France and Greece are the starting point for drawings transforming reality by poetical devices to explore how the meeting with alienness is managed. Referencing the fables of Jean de La Fontaine, humans are turned into animals. Portraying a mighty exodus, RRH’s images question subjects like identification and empathy.

The Iranian artists’ collective RRH lives in self-imposed exile in Dubai. The trio’s work explores homelessness and exile as lived experiences. The drawings depict the European refugee crisis from 2015 on as a tragic diaspora of mythic proportions. In a demanding, manual process, the three artists paint collaboratively on top of newspaper photos and clips from TV and YouTube. Refugee camps in France and Greece are the starting point for drawings transforming reality by poetical devices to explore how the meeting with alienness is managed. Referencing the fables of Jean de La Fontaine, humans are turned into animals. Portraying a mighty exodus, RRH’s images question subjects like identification and empathy.

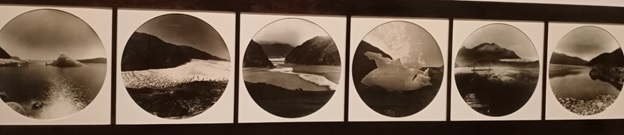

Marianne Engberg is a pioneering figure in the pinhole technique, and her pictures from Greenland are reminiscent of Danish-Greenlandic Artist Pia Arke’s works. Technically superb, Engberg’s images seem to embrace the present moment and eternity alike – provided that one ignores the fact that they are a result of light falling in through a very small hole over time. The conquests made by the pioneer tradition-within the realms of photography and territorial exploration alike – are at stake in these black-and-white images, but so too is experimental freedom. The camera was made out of two lids from oatmeal cans, and there is no optical viewfinder in the box, meaning that the artist cannot see the subject being depicted. The results rely entirely on Engberg’s gut feeling and her hand’s coordinated placement of the device at specific points in the landscape.

Marianne Engberg is a pioneering figure in the pinhole technique, and her pictures from Greenland are reminiscent of Danish-Greenlandic Artist Pia Arke’s works. Technically superb, Engberg’s images seem to embrace the present moment and eternity alike – provided that one ignores the fact that they are a result of light falling in through a very small hole over time. The conquests made by the pioneer tradition-within the realms of photography and territorial exploration alike – are at stake in these black-and-white images, but so too is experimental freedom. The camera was made out of two lids from oatmeal cans, and there is no optical viewfinder in the box, meaning that the artist cannot see the subject being depicted. The results rely entirely on Engberg’s gut feeling and her hand’s coordinated placement of the device at specific points in the landscape.

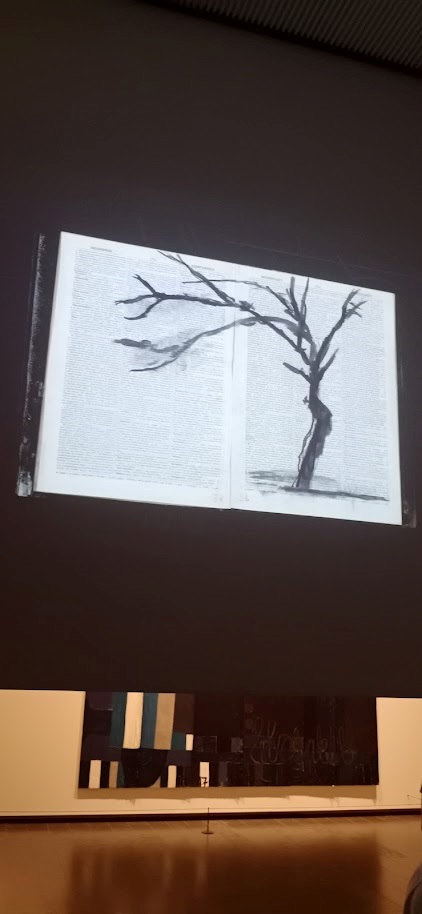

Black Box/Chambre Noire, one of Kentridge’s absolute key works, represents a dramatic new direction in the artist’s work at a time when he increases formal complexity. The work is based on the artist’s set designs and visuals for a production of Mozart’s opera “The Magic Flute” (1791).

Black Box/Chambre Noire, one of Kentridge’s absolute key works, represents a dramatic new direction in the artist’s work at a time when he increases formal complexity. The work is based on the artist’s set designs and visuals for a production of Mozart’s opera “The Magic Flute” (1791).

The work depicts an event that is arguably one of the first genocides of the twentieth century. In 1904, in South West Africa today’s Namibia) German colonial forces brutally suppressed a rebellion of local tribes. In one case, the Germans killed 75 percent of the Herero tribe Kantridge examines this historical event partly through the Freudian concept of Trauerarbeit (work of mourning a work that never ends, interwoven with the artist’s invariable, self-reflexive study of process and meaning Black Box/Chambre Noire shows us the engines of representation. We show subjective experience is constructed as one big true narrative Resisting finally the work questions single historical constructions.

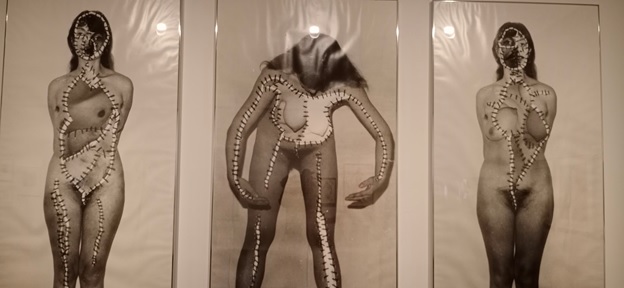

Annegret Soltau’s “Body Intervention” was created while the artist was pregnant with her daughter. The photographs, which depict the artist, were taken by her husband with a single 35mm camera. The photographs have been torn to pieces and the parts sewn back together with black thread to form three small photo montages. These montages were subsequently enlarged to more than life-size, imbuing the work with a strong monumentality and insistent physical presence. Annegret Soltau was two months pregnant at the time, a condition she references in the central image with a pose in which long arms cradle the growing belly. The photographic triptych expresses the inevitable physical changes and conflicting emotions associated with the metamorphosis from being a woman to becoming a woman and a mother.

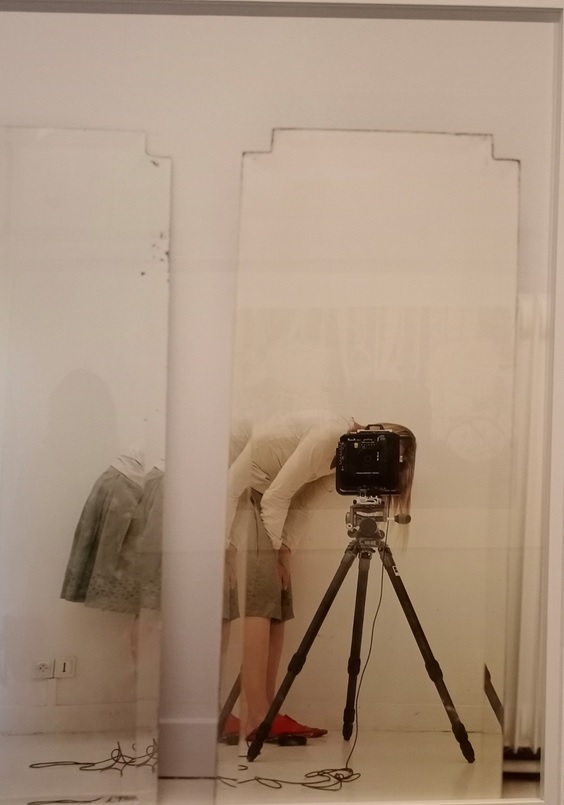

Ever since the beginning of her career in the early 1990s, Elina Brotherus’s works have consistently revolved around a single recurring figure the artist herself. The choice is not moted by narcissism, but by practical considerations: the model is always available, ready to pose before the artist’s camera. It is also an example of feminism in the practice-a of a woman observing a female subject. The group of works by Brotherus acquired by the museum allows observers to follow the shifts occurring In her themes and motivic explorations-always with herself as the model. Self-portraits become fictional portraits, and a range of other principles are introduced incorporating other artists and their practices.

European museums provide a holistic experience including the display of visual art in a way that keeps visitors involved and their theatrical installations and explorations spellbind the human mind. Here the artwork not only interacts with the observers but also become part of the life of the visitors.