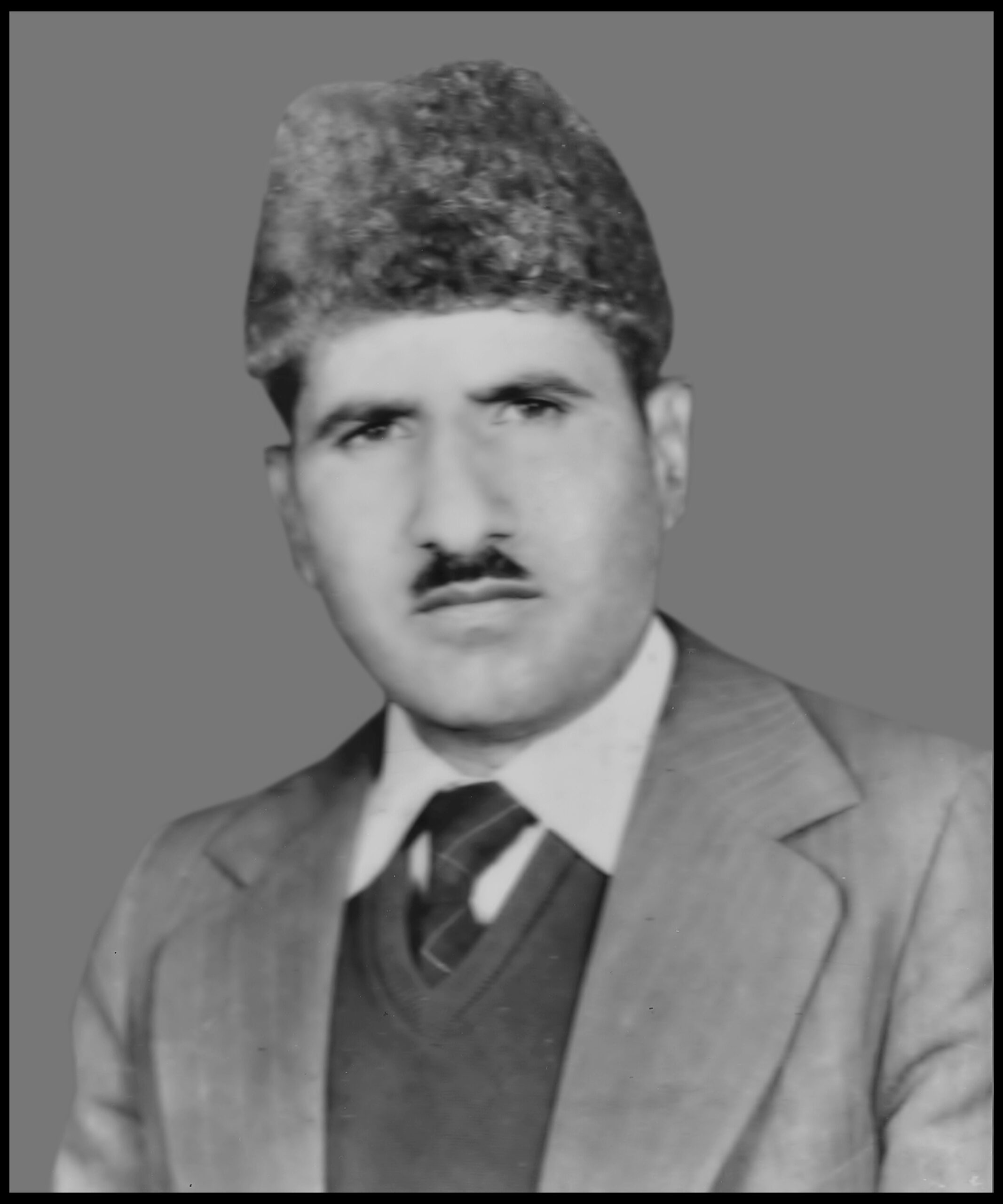

Editor’s Note: This article written by Dr. Fozia Kamran Cheema is published in connection with the 6th death Anniversary of her late Father Muhammad Anwer Cheema.

“Fozia father has left” (Fozia abu chalay gaiy) …. was the voice message I received on November 8, 2021, from one of my soulmates like dear friends.

It was six, o clock in the morning and I was half slept. I came immediately into my senses and recalled myself stating the same sentence on November 22, 2015.

I reminisced that night, as it was yesterday. I was alone in the ambulance with my father’s dead body, my brother was in a car in front of the ambulance. Driver stopped at Kharian Cantt army Check Post and before somebody even asked me anything, I told abruptly ….” meray abu chalay gaiy” (my father has left) to the soldiers standing on the Check Post.

What kind of sentence is that? It does not fit any rule of grammar …foute nahen howay, bas chalay gaiy (he did not die, he just left). Strange semiotics, an unusual set of words.

Now, after a couple of years of my father’s loss of life and after hearing to the same exact sentence from everyone who underwent the loss of father, I can find a pattern in it. I can locate the same form of denial. I get to see not acknowledging the truth and still longing for the possibility that father will return, will be there like he always was, will continue on guarding our backs.

There are millions of kinds of sorrows in the world, and each one has its specific appearance, own structure, personal chemistry, individual arrangement, own morphology, and distinctive set of building blocks. It is practically impossible to compare one wound to the other. People have their own unique set of grieves, even though they have experienced the exact same trauma. There is always a minuscule fraction of variation. There is every time a contrast or a comparison. There is almost all the time a teensy tiny lack of empathy in form of my grief is superior to others, is inimitable, is, precious, is one of a kind, and is much more damaging than anyone else’s. This competition makes it tough to understand each other’s miseries, sentiments, and pains.

Similar losses produce dissimilar coping mechanisms. Identical injuries manufacture different kinds of pains and the variable period of time before that pain becomes chronic. The same obstacles tailors not the same solutions.

Analogous grieves — yet miscellaneous degrees of torments, unalike ways of seeking help, varied choices, altered styles of victim playing, diverse paths of healing—if healing even is possible ever.

Even though no two mourns are akin to each other, however every defeat, each forfeiture, all heartaches, and every single loss follows all the stages of grief theory—nevertheless in its own exclusive manner. It starts with shock and denial, abruptly jumps to pain and anger, then bargaining, and later sluggishly grows into depression and in many cases after a period of time into Acceptance.

The heartache of losing a father is not at all similar to any other kind of loss in this universe. It starts different, it evolves distinctive, and it ends divergent.

Unlike all other aches and anguishes, it is equivalent and comparable. Other’s father’s death is not less significant than mine. My father left is as crucial as anyone else’s father has left. It is identical, exactly the same. The moment we hear it, we recognize the pain, we realize the damage— an irremediable one. No difference in grief pattern either, ten years old or sixty years old–an orphan is an orphan. No comparison of my father dying at seventy-nine versus others at fifty or my father dying suddenly against others after a prolonged illness, neither rivalry nor contest.

Departing of the fathers remains the same —the constant, regardless of all the variables around.

In a world filled with trillions of brands of mislays and distresses, losing a father has an un-distinguishable impact on every single individual. It generates the matching feeling of being left alone in a crowded place and similar apprehension of never ever receiving the same love again . Flames in the heartburn alike, sudden removal of shoes in the desert heat are comparable, non-quenching thirst feels familiar, same murky thoughts, same misery and shame of not doing enough for departed is bonding. A nonstop feeling of hasty loss of shelter in a thunder-filled snowy December night where all paths and roads are blocked makes us a squad, the hefty burden of mountains on our shoulders connects us.

This grief has the same gravity, it has the same center of gravity.

Oddly, this woe does not trail the theory of grief. Yes, it starts with the ultimate denial of my father left (meray abu chaay gaiy) and we hope that the first man, the only man in our life will come back and will keep on loving us, guiding, and protecting us. But right after the first stage, this grief differs from all other losses, as it skips the pain, the anger, the bargaining, and the depression and directly lands into Acceptance …

As a pain specialist, this path makes sense to me. This shortcut of switching from denial to acceptance in this particular loss is inevitable. Going through every phase of grief is a luxury not affordable after the death of the father.

Fathers of the East, while they are still living are the most undervalued individuals in our stories—Their songs are seldom sung, and their examples are rarely given.

Mothers of the East, particularly the mothers of Central Asia are the main charm of each folk tale. I am definitely not denying the sacrifices of mothers, but in eastern cultures, she triumphs everything. We put our mothers on pedestals and many times in doing so, we compromise the role of father. Giving him less admiration and not giving him the acknowledgment of what he does for us —not idolizing him, and not showing our love to him has somehow become a crucial part of the “we love our mother the most” package.

We only acknowledge the tears of our mother and totally forget about the not revealed burdens of our fathers. We remember soft mole walay parathay and ironed uniforms by our mothers, but we don’t exhibit regard to bruised feet of our fathers in the voyage of supplying those mole walay parathay and clean uniforms.

We write poems about the lemon water given by mothers after a long school day, and we basically disremember to acknowledge— kah kitnay kantay us rastay kah us society kah , logown kah tanown kah , hamaray bap nain apnay hathown sah chunay hon gay jo hamray school ko jata tha (we don’t mention the effort our fathers put in smoothing the paths to our schools). Fathers are almost always category B actors, infrequently on the scenes, yet always behind the scenes.

When my father left unexpectedly and suddenly, the eyes of my heart opened up eventually. I saw for the first time that five rupees handkerchief in the pocket of his old numerous times used hand sewed waistcoat. I noticed for the first time his feet, discolored, tired, and wrinkled. As he was resting in hospital, I recalled he never slept for more than a few hours in the nights I remembered.

For the first time, he told me the story of his life with his eyes closed, with his lips hushed and him inhaling heavily through machines. He revealed everything to me without uttering a single word. One orphan spoke his heart out to another orphan …so I understood him absolutely and instantly.

My acquired blindness and deafness quickly shifted into the gravest of appreciation and insight.

With his leaving, I grasped the fact that I also had lost the comfort of demonstrating my emotions.… Therefore, I expressed no pain, I uncovered no anger, whom to bargain with? depression seemed worthless too…. I skipped every stage of grief and leaped straight into Acceptance.

The receiver of all those emotions had left (meray lad uthanay wala chala gay tha). The man of my life had departed—forever.

The person sitting on the dirty floor of Khanewal station the whole night and giving the entire bench to his sleepy daughter was faded out, the man waiting on the warm stairs of Riwaz academy for hours and hours while the daughter was inside learning, had closed his eyes for a good peaceful sleep. The person stepping out of the car and holding his motion-sicked chubby daughter in his lap from Wazirabad to Gujrat was never coming back.

Meraay abu chalay gaiy thay, kabhe na anay kah liay … I learned all the hard teachings of life sitting beside him in that ambulance. That journey from Kharain to Gujrat altered me eternally. Sound of the ambulance, me, him and dark and never-ending lonely G-T road, everything else vanished away, simply disappeared.

I opted not to be selfish any longer. I left his hands —-I liberated him. His soul deserved to travel peacefully, delightfully, and baggage-free.

I left his hands and I whispered—Father you owe me nonentity and nothing at all. You don’t have to watch over for me anymore, you must not care about my problems any longer, don’t even come into my dreams to meet me… You have done sufficient, you have empowered me enough that I can walk my path now, you have guided me adequate to not be to be misguided by anyone. You have taught me ample, and I pledge I will spread the light onwards, you have inspired me in a manner that I myself can be an inspiration, you have loved me plenty and my vessel is completely filled—You have done more than necessary. You were awake for a while, today starts your time to sleep peaceably.

Let me kiss your feet for one final time before you walk towards the track unseen and trails unscathed.

But he was a father and fathers do not leave behind their little girls alone. He did not go, he stayed.

My father chose my heart to live (Meray abu nain rahnay kah lia mera dil chun lia ).

His presence never became absence again, his fragrance never faded away, doorbells never rang again, as my visitor never left.

He remains with me, he breathes with me, he lives through me. He whispers constant prayers (duas) into my ears, he keeps on holding my hand and dreams the most gorgeous dreams with me. He continues to watch on me, even though he owes me nothing any longer.

He applauds for me …He pats my back …He is the eternal resident of my heart, and we visit the territories unseen together.

The residents of the hearts make us courageous, resilient, and indestructible—they eliminate our fears. We smile their smiles, and they are so generous that they let us live their lives and dream their dreams too, and never a nightmare ever again.

They fold the whole globe in between their palms and make the world so insignificant and so easy to ignore, they make us knowledgeable of not being led by the world.

The heart finds the greatest comfort, it knows that residents will never go away, as they have paid the price of their lives to be in our hearts.

The residents get planted in our hearts and after finally getting our full consideration blossom into a whole new existence, a whole new life —-lasting for all times.

Our fathers, our inhabitants give us the one-of-a-kind opportunity of going through all phases of our rare grief at our personal pace, in our particular tempo. They help us in coming out of shock, they soothe our pains into profits, they bargain the finest bargains with us, they take all the regrets and modify them into meanings. The meaning of our life, the purpose of our being, the path towards the destiny, towards the growth —Forwards begins there, then, with them.

Note: Dr. Fozia Kamran Cheema is a pain management physiotherapist at Copenhagen University Hospital, Copenhagen Denmark. She can be reached at her Twitter @ZayaFo